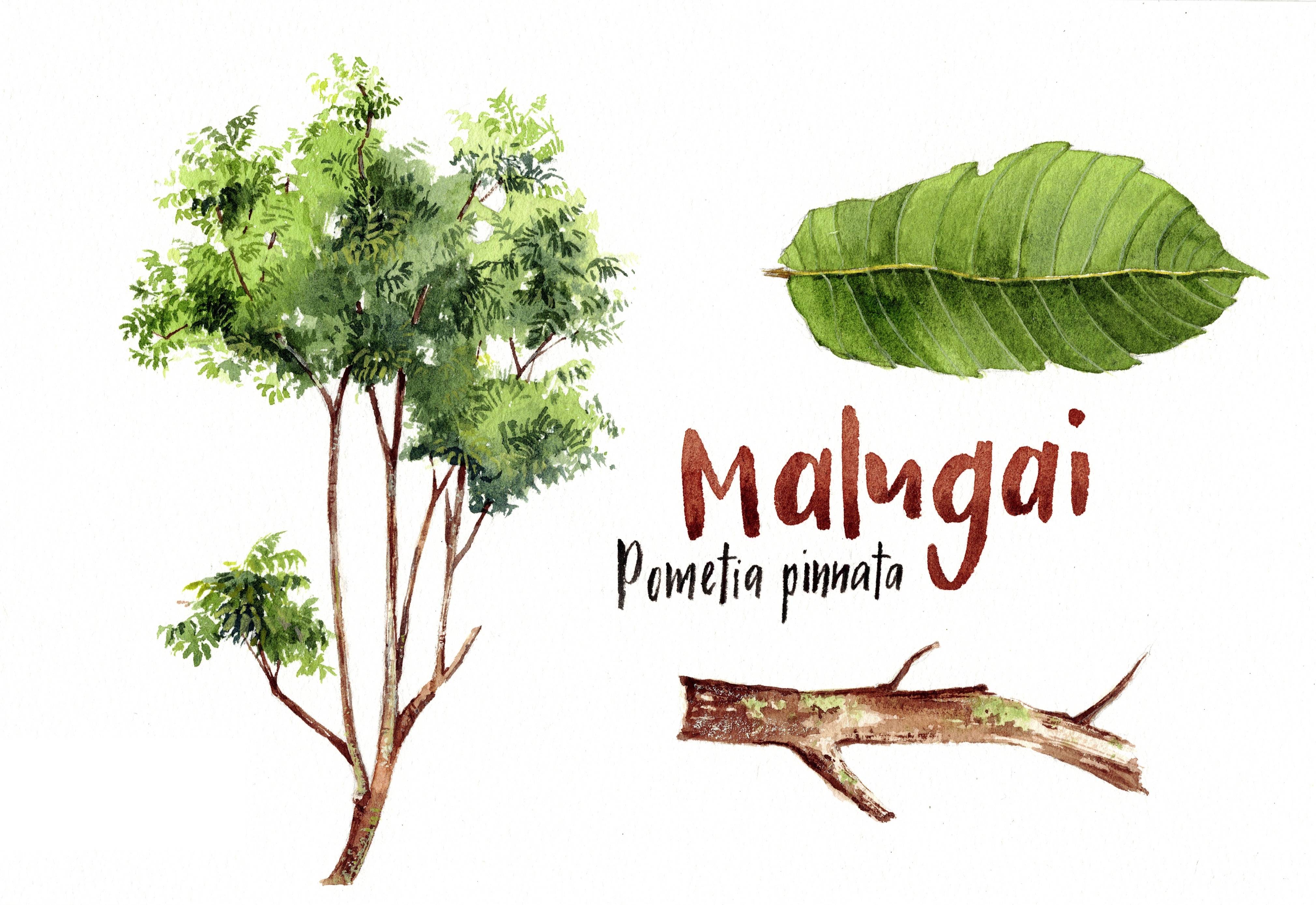

Malugai (Pometia pinnata), a tropical hardwood tree worth farming for its general-purpose wood, and is also considered an attractive ornamental plant. Has edible fruit similar to lychee and rambutan. Its leaves, bark, and sap have various antiseptic and analgesic properties, and are used in folk medicine.

Malugai (Pometia pinnata), a tropical hardwood tree worth farming for its general-purpose wood, and is also considered an attractive ornamental plant. Has edible fruit similar to lychee and rambutan. Its leaves, bark, and sap have various antiseptic and analgesic properties, and are used in folk medicine. Negrense lore has always held that Negros Occidental is a naturally hilly region (the name “Bacolod” supposedly comes from “buklod” or “hill”) and, therefore, is not prone to flooding. Recent years have belied this, with reports of devastating floods becoming commonplace during typhoon season. However, while climate change has made weather disturbances more intense and extreme globally, flooding can also be caused by a phenomenon closer to home: deforestation.

Besides producing fresh oxygen, trees can absorb and store massive amounts of water, releasing it back to the atmosphere in trickles over decades. Their root systems create underground reinforcing networks that hold land in place, preventing erosion and mudslides. Deforested areas flatten over time, suffering the loss of fertile topsoil, and become regularly flooded during the rainy season.

While the cities of Negros Occidental have moved with the times and become fairly urbanized, generous portions of the province remain wild, if not exactly virginal. However, with the steady increase in population and the encroachment of big extractive and polluting industries, these natural preserves are in danger of gradually disappearing, as they have in other “progressive” provinces in the Philippines.

The largest forest ecosystem on Negros Island can be found on the northern and northwestern slopes of the Kanlaon mountain range. It is composed of three discrete but contiguous areas—Mount Kanlaon Natural Park, the Bago River Watershed, and the Northern Negros Natural Park (NNNP)—totaling some 150,000 hectares of forest land combined. The Department of Environment and Natural Resources reports that the total forest cover in these priority areas was at 19.2%, or some 39,000 hectares, in 2010. Each year 2,400 hectares of forest are degraded, resulting in a net forest loss of at least 290 hectares per year. Natural parks are designated and protected by law, but they are constantly under threat from human activity, both legal and illegal.

Narra (Pterocarpus indicus), the national tree of the Philippines. A threatened species because it is highly prized for its beautiful and durable wood, used in furniture and home interiors. Very resilient, adaptable, and easy to plant and grow. An excellent shade tree.

Narra (Pterocarpus indicus), the national tree of the Philippines. A threatened species because it is highly prized for its beautiful and durable wood, used in furniture and home interiors. Very resilient, adaptable, and easy to plant and grow. An excellent shade tree.Apart from logging and mining, two industries which cause considerable damage to the environment, agriculture, urbanization, and real estate development also impact nature preserves. With human population growth comes the need for viable living spaces, and as cities and suburbs become overcrowded, there rises the demand for green open spaces to escape to on vacation getaways. Large swaths of Negros Occidental’s virgin forests have been converted into agricultural land, commercial districts, residential areas, and leisure facilities over the centuries, and the pace of these changes has only sped up in recent years. Sometimes progress and development exacts its own tolls—one of the current threats to the integrity of the NNNP is a highway that would connect Silay City and the municipality of Calatrava, cutting through Cadiz City. While undoubtedly useful, perhaps even necessary, its construction will result in further reduction of already diminished forest land.

Forest degradation also comes about from “smaller” human activity, such as unsustainable fuel-wood collection, illegal hunting and poaching, and human settlement.

Kalumpit (Terminalia microcarpa), a tall, wide-spreading hardwood tree. Its timber is very durable when used indoors for furniture, flooring, or cabinets. Its plum-like fruit has a sour-sweet tartness and can be used to make jams and wines.

Kalumpit (Terminalia microcarpa), a tall, wide-spreading hardwood tree. Its timber is very durable when used indoors for furniture, flooring, or cabinets. Its plum-like fruit has a sour-sweet tartness and can be used to make jams and wines.

Just as the rest of the world harkens to the call to rescue the environment from total destruction, Negros Occidental also needs to step up the restoration, preservation, and protection of its natural resources, primarily its precious forests.

The Negros Forest Park (NFP) is something of an anomaly in the urbanscape of Bacolod’s city center. Many residents aren’t even aware of its existence, but it’s been in its current location—just across the street from the southern end of the Provincial Capitol—since 1986. Amid the paved and manicured environs of kilometer zero, the NFP looks like an overgrown, neglected space that would be highly prized by local realtors, given its location.

Within its unassuming borders though, Mother Nature takes a stand with the help of a few human advocates and volunteers.

Once run by Negros Forest Ecological Foundation, NFP began with a simple but important mission: the saving of endemic endangered species through captive breeding and cultivation, as well as reforestation and conservation education. It has since expanded its goals to include the building of protection capacity among forest wardens and implementing conservation laws.

Makaasim/Udling (Syzygium nitidum), a tall tree with gray-brown wood. Harvested primarily for its timber, which is used for general construction, furniture, ship building, and wooden implements. One of two threatened species that are being conserved through cloning in a Department of Science and Technology project.

Makaasim/Udling (Syzygium nitidum), a tall tree with gray-brown wood. Harvested primarily for its timber, which is used for general construction, furniture, ship building, and wooden implements. One of two threatened species that are being conserved through cloning in a Department of Science and Technology project.

NFP is now managed by Talarak Foundation, a private sector environmental organization established in 2009. Since its creation, NFP has successfully saved endangered animal species endemic to Negros, including two varieties of hornbill, the Negros Bleeding Heart Pigeon, the Visayan Warty Pig, and the Visayan Spotted Deer. The curator of NFP’s Biodiversity Curation Center, David Garcia Castor, received the Negros Occidental Governor’s Conservation Achievement Award last year for his decades-long fight to protect Negros flora and fauna. (Negros Season of Culture covered Negros Forest Park’s animal conservation efforts in this video: Negros Forest Park’s Sexy Big Five)

Today, the park is the last remaining endemic green space in Bacolod City, despite repeated attempts to overturn its mandate and convert the space into something more productive and profitable in an urban context: parking lot, office building, shopping center. In addition to the 150 animals that call it home, there are 26 species of hardwood and fruit trees. As such, it is a carbon sink, oxygen generator, watershed, and living museum right in the middle of Bacolod City.

From this center, NFP works with local environmental protection groups, such as the Negros Environmental Watch, to ensure the continued viability of the province’s diminishing natural resources.

In its mission to protect and conserve the Negros ecosystem, NFP does more than showcase the variety of native trees on the island. It strives to educate Negrenses on how best to restore forest land through the planting of trees endemic to Negros.

Trees classified as “endemic” are found exclusively in a particular country or region, and may perhaps have originated in those places. “Indigenous” trees comprise a larger group of species native to a broader, more generalized area, and can be found in many countries and regions.

Although many species can thrive in various places with different climates and natural conditions, endemic species grow best in their places of origin and have natural relationships with elements of the surrounding ecosystems. Their root systems grow deeper into the ground, and they have beneficial effects on other plant life.

Garuga (Garuga floribunda), a tall, large deciduous canopy tree. Most valued for its timber, which is used in general construction, furniture, veneers, and plywood. Also used to make other types of wood products (toys, sports equipment, domestic woodwork). It has edible fruit, produces a dye, and is sometimes used in folk medicine.

Garuga (Garuga floribunda), a tall, large deciduous canopy tree. Most valued for its timber, which is used in general construction, furniture, veneers, and plywood. Also used to make other types of wood products (toys, sports equipment, domestic woodwork). It has edible fruit, produces a dye, and is sometimes used in folk medicine.

Human travel over the millennia has resulted in the migration of natural resources including flora and fauna, and plants and animals have been successfully propagated in foreign locations. Such foreign or exotic species may provide certain benefits in ecosystems and societies to which they are introduced, but on the whole, they constitute disruptions to the native environment.

For instance, while exotic trees may seem a relatively benign element to introduce to an environment, they can cause lasting damage to the ecosystem. They can strain a water supply, degrade the local water table, and compete with local plants for nutrients. They can also alter the chemical composition of the soil they grow in, not always for the better. Most significantly, they have no existing natural relationships with the local wildlife, which tend to seek out familiar native species for shelter, nutrition, and other needs. For this reason, exotic trees tend to be eerily quiet, because they attract and harbor no local animals or insects.

NFP advocates mindful reforestation, or the selection of only endemic species to plant and propagate in deforested areas, or to cultivate for commercial purposes. The park not only showcases these endemic species, providing information on their uses and benefits, but also makes seedlings available for sale to organizations and individuals seeking to plant trees.

NFP currently provides seedlings of seven endemic tree species: Malugai (Pometia pinnata), Narra (Pterocarpus indicus), Kalumpit (Terminalia microcarpa

), Udling or Makaasim (Syzygium nitidum), Garuga (Garuga floribunda), Bugnai (Antidesma bunius), and Bakan (Litsea philippinensis).

Bugnai (Antidesma bunius), the Philippine native berry, which makes a popular delicious wine. An evergreen ornamental tree ideal for screening, windbreak, and regreening. Very easy to plant and propagate.

Bugnai (Antidesma bunius), the Philippine native berry, which makes a popular delicious wine. An evergreen ornamental tree ideal for screening, windbreak, and regreening. Very easy to plant and propagate.Of these, Narra and Udling/Makaasim are classified as threatened species as of 2017, and are protected and regulated under Philippine law.

Individuals and organizations interested in planting and cultivating trees in Negros Occidental are strongly encouraged to limit themselves to endemic tree species, such as those listed above, which are highly valued for their wood and beneficial to the local ecosystem. Landowners are advised to consider leaving portions of their estates uncultivated and undeveloped, allowing these to add to the green spaces of the province.

Above all, Negrenses must become aware of how connected their modern lives are to the natural environment that surrounds them, no matter how distant and irrelevant it seems. We may all live in urbanized spaces, but our own survival depends on the health and well-being of the earth. The sooner we recognize this, the likelier it is that Negros Occidental will once again be flood-free.

Bakan (Litsea philippinensis), a tall evergreen tree with somewhat soft wood. Often used for sculptures, especially of religious or sacred images. Also suitable for decorative paneling, furniture, and cabinets, as well as plywood.

Bakan (Litsea philippinensis), a tall evergreen tree with somewhat soft wood. Often used for sculptures, especially of religious or sacred images. Also suitable for decorative paneling, furniture, and cabinets, as well as plywood.Text by: Vince Groyon

Illustrations by: Erika M. Velasco

Sources:

Fern, Ken. Useful Tropical Plants Database 2014. http://tropical.theferns.info/

De Jesus, Amado. “Why We Need to Plant Native Philippine Trees.” The Philippine Daily Inquirer, 6 March 2021. https://business.inquirer.net/319013/why-we-need-to-plant-native-philippine-trees